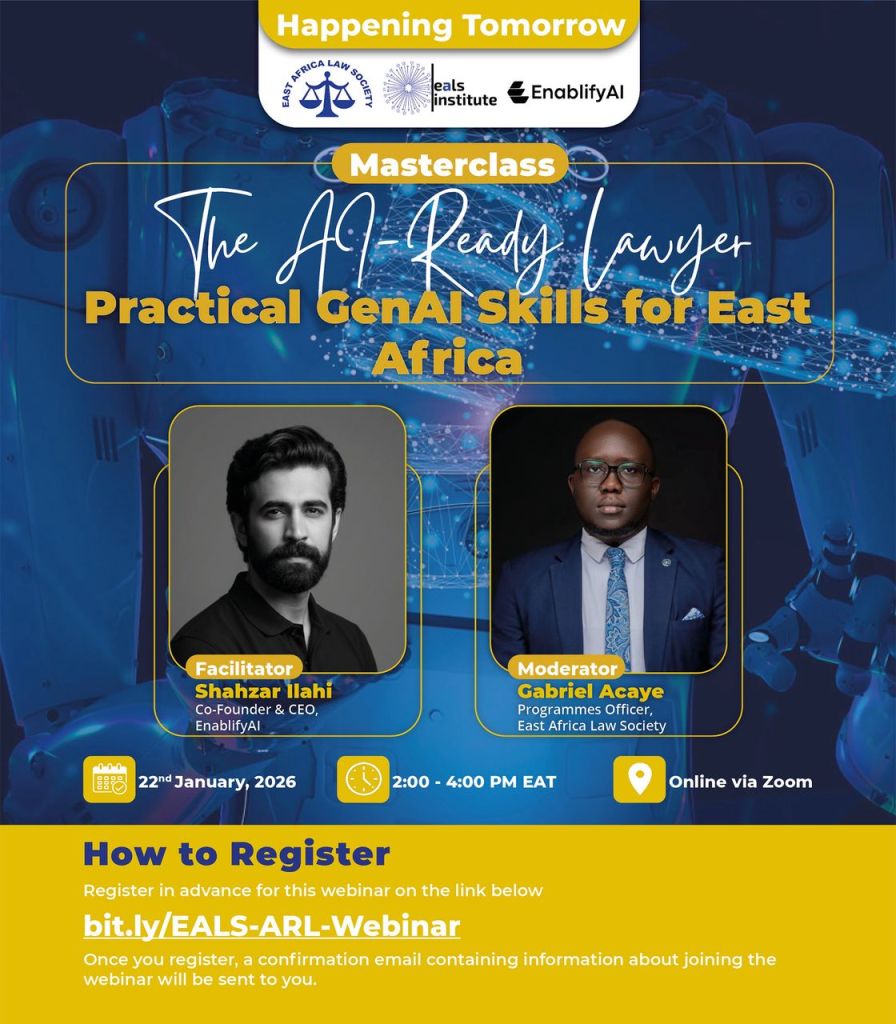

On 22nd January, 2026, the East Africa Law Society convened its first webinar of the year under the theme “The AI-Ready Lawyer: Practical GenAI Skills for East Africa,” bringing together legal professionals from across the region for a candid and hands-on conversation about the future of legal practice. The session was moderated by Gabriel Acaye, Programmes Officer at the East Africa Law Society, who welcomed participants on behalf of the Society’s leadership and set a clear tone for the discussion. He noted that artificial intelligence was no longer a theoretical or emerging concept for the legal profession, but a present and rapidly evolving reality already reshaping how law is practiced. The purpose of the session, he explained, was not to dwell on trends or hype, but to focus on how lawyers were responding in real time, and whether they were doing so competently, safely, and ethically. He emphasized that the master class was designed to equip lawyers with practical, immediately usable skills, positioning them to become AI-ready rather than AI-dependent, technologically capable while still grounded in professional standards and judgment. He also noted that the webinar served as a precursor to a physical master class scheduled to take place in Nairobi in March 2026, organized in partnership with Enablify.

The facilitator, Shahzar Ilahi, Co-Founder of Enablify, began by situating the discussion within a global context, observing that East Africa had shown remarkable openness to technological adoption, including early uptake of generative AI tools. He cautioned that the legal profession was already experiencing disruption at a pace rarely seen in previous technological shifts, describing artificial intelligence not simply as a new tool, but as a behavioural and structural change in how professional work is done. Drawing on insights from Professor Richard Susskind, adviser to the UK Supreme Court on AI and law, he underscored that markets tend to show little loyalty to traditional methods if faster, cheaper, and better alternatives exist. This tension, he noted, left lawyers both inspired by new possibilities and unsettled by the speed of change.

Shahzar illustrated this disruption through concrete examples, including his own experience of public resistance when he predicted that lawyers who failed to adapt to AI would become irrelevant within a decade — a position that was later echoed in a Supreme Court of Pakistan judgment. He pointed to developments in the Middle East, where AI-driven court systems were being introduced to process disputes digitally, generate preliminary judgments, assess probabilities of success, and divert matters to mediation or settlement where appropriate. While acknowledging the debates surrounding such systems, he emphasized that their deployment signaled an irreversible shift. He supported this with data showing dramatic increases in daily and hourly AI use by lawyers within a short time span, alongside a steep decline in entry-level legal roles globally. The issue, he stressed, was not the replacement of lawyers per se, but the replacement of lawyers who lacked the skills to work effectively with artificial intelligence.

To ground the discussion, Shahzar walked participants through what artificial intelligence actually is and how it works, tracing its origins back to the 1940s and the work of Alan Turing. He explained that tools like ChatGPT were applications of a much older technology, and reminded participants that they had long been interacting with and training AI systems through everyday digital activities such as image verification, predictive text, and facial recognition. He drew parallels between human intelligence and machine learning, explaining how both rely on data acquisition, pattern recognition, storage, and output. The key distinction, he noted, lay in scale: machines could ingest and process volumes of information far beyond human capacity, at extraordinary speed.

Building on this foundation, Shahzar introduced generative artificial intelligence as a category focused on producing outputs — text, images, video, analysis — from user inputs. Through live demonstrations, he showed how widely accessible tools could generate professional visuals, videos, websites, legal summaries, timelines, and learning materials in minutes, tasks that would traditionally take hours or days. He emphasized that the real value for lawyers lay not in replacing legal reasoning, but in automating routine, time-consuming tasks, allowing practitioners to focus on strategy, judgment, and client engagement. He also cautioned participants about risks such as hallucinations, confidentiality breaches, and over-reliance, stressing the importance of controlled use, proper prompting, and ethical safeguards.

Throughout the session, Shahzar returned to a central message: artificial intelligence was already embedded in the legal ecosystem, and the responsibility now lay with lawyers to understand it well enough to use it responsibly. The master class, he concluded, was not about turning lawyers into technologists, but about ensuring they remained relevant, effective, and future-facing in a profession undergoing profound transformation.

For more, please watch full video: https://www.youtube.com/live/NnUtQHZZr60

Leave a comment